Sometimes it happens that you are in a matrix organization and might have two managers with (somewhat) overlapping areas of responsibility. This is not necessary a bad thing. For once, it is a great opportunity to open your eyes and learn from the situation, either as the employee with two managers or as one of the two managers of the employee. As everyone is bringing different expertise and points of view to the table, higher quality insights, learning and decisions will surface. However, it might be at times painful, especially when trust is not fully formed between the involved parties.

Here are some guidelines I found useful:

- It is critical for the two managers to get along very well and not to try to get advantages one over the other. Think child with two parents. Even for the most well intended people, misalignment will occur and trust will be eroded if the two managers don't take special care to continuously build and cherish a trust relationship between themselves. Relationships are not to be taken for granted. Work is needed to build a maintain a relationship between two people.

- It is highly recommended for the two managers to align between themselves on the roles and responsibilities of each other and re-discuss these from time to time. Understanding might drift as new situations and challenges arise.

- Try to avoid the communication triangle and rather aim for the star.

In triangle communication, each two people have a separate communication channel, meaning they have separate meetings without a common tripartite alignment process. In the star communication, all three meet regularly all together and they reconfirm their understanding. This latter setup drastically lowers the risk of misunderstanding and / or of the child with two conflicting parents situation.

On what I call the airplane model of organization design

I have a strong belief that people have a great capacity to take the right decisions provided that they have the freedom to do so and the right information easily accessible. When I am thinking about organization design I am centering it around what I call "the airplane model". The model itself is simple: the individual is in its center (the pilot). The rest of the organization is there to support him take the right decisions (the instrument panels in the cockpit, easily accessible). Beside the empowerment and motivation that comes from such a setup, of being in control of the course of your work, the model has some other less obvious advantages:

- It scales. The pilot is everyone and everyone is flying its own plane supported by others. The programmer codes while the team-lead helps him get access to knowledge (architects, websites, classes, conferences), tools (task boards, IDEs, code metrics, continuous integration servers) and goals. The team-lead leads while his manager offers insights, perspectives, a sounding board, access to resources, confidence, the program manager access to configured Jiras, QA to product metrics and so on.

- It mandates collaboration and knowledge sharing because the underlying assumption is that nobody flies blind. Decisions are fully owned, but checking the instruments (discuss, check metrics) is a must.

- It is a quest for continuous improvement: always simplify access to information, always discuss, interpret metrics or discard irrelevant ones. Bad decisions can happen and they are expected as long as we learn from them, but ignorance is not permitted. I personally am OK with any decision as long as I have the certitude that all factors have been properly weighted.

On compound interest and organization design

In any management endeavor, initial conditions matter greatly but they can be beaten given some conditions occur. However, beating the averages is a hard job. Given the fact that growth and decision making at any point in time are random variables normally distributed around the system's average, usually the system beats the individuals, thus organization design is critical for a successful growth.

A little bit about compound interest and exponential growth:

Let's consider the following two cases of growth:

First case:

Initial condition: 1 and 4 respectively, same exponential growth of 1.7. It is obvious that the initial 1:4 factor is preserved and the difference is only amplified as time passes.

Second case:

Same initial condition 1:4, but this time exponential growth is set to 2 to 1.7. After roughly 10 periods, the initial advantage of the second series is completely lost and from here on the difference grows at an exponential rate in favor of the first. This means that it takes time to recover, but once the gap is recovered, the first series obliterates the second.

But how do we translate these results to day to day management thinking?

Obviously, the initial conditions matters. A company or a team with more funding, better trained people, more connections or that simply starts earlier has a clear advantage over a less fortunate competitor. Because the less fortunate competitor needs time to recover, he may simply run out of business before the gap is closed, even in case of perfect execution. However, once the gap is closed, better execution gives much higher yields.

So the main question is, provided that we have enough funding to survive, how do we increase the exponent? I think the exponent has three defining characteristics: ability to learn, to execute and to incorporate learning back into execution. To learn means to experiment, to play. That means a culture willing to tolerate failure and learn from it and willing to invest in people - to give them space, freedom of self expression, a "let's try attitude". It means a culture with fewer ties and dependencies, with simpler checks and balances, ones that trusts their employees that they are capable to solve problems and learn from mistakes. It means a culture that requires dialogue but abstains itself from being prescriptive. To me, these goals are well met by the airplane model described above.

Initiative is fragile. Push an employee too much to explain himself, to give too much proof that he is right or punish him (even slightly) for small mistakes and the initiative is gone. Next time he will just wait to be told what to do.

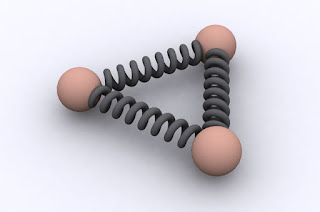

I imagine organizations and management lines as meshes of masses connected through springs. The more ties a mass has and the stronger the springs, the lower the movement ability an individual has. And with the lower movement ability, the exponent described above (a function of the ability of the individual to excel in a given context) simply converges to the comfortable average, while the whole system slows down due to lost energy to friction.

Closing thoughts:

The article describes three roughly independent management ideas centered around organization design. There is a red line though. That is systems (of humans) are not to be taken for granted. It is not enough to have the brightest in the room to get results. How you organize them, how you make them communicate (and in humans communication is extremely expensive and tricky due to the low bandwidth of conscientious thought and speak and due to the whole set of unspoken assumptions and emotions involved), how do you setup systems with enough degrees of movement to maintain individual initiative and still have some control over the direction of flow is what gives the higher returns. And all these are layered on a leadership style that must be humble, willing to listen and to point people in the right directions, not for completing tasks, but rather for gathering information and learning, and then have them take their own decisions with confidence.

No comments:

Post a Comment